September 18, 2015

Cardio Workout Friday With Carol Strom Day 7 of 21 day challenge.

June 2, 2011

The myth of ripped muscles and calorie burns

Weight training can build muscle, but that doesn't mean you start burning calories like a Hummer burns gasoline. (Mark Boster, Los Angeles Times / May 16, 2011)

Sorry to say, but gaining muscle doesn’t make your metabolism skyrocket. Put down that Haagen-Dazs.

Whenever I hear about some amazing way to boost resting metabolism, my male-bovine-droppings detector goes berserk. Take the perennially popular one stating that 1 pound of muscle burns an extra 50 calories a day while at rest — so if you gain 10 pounds of muscle, your resting metabolic rate (RMR) soars by an extra 500 calories each day.

Awesome!

And also drivel. I’m more likely to believe bears use Porta-Potties and the pope is a Wiccan.

Though its origins are uncertain, any number of fitness magazines have made the “50 calories per pound of muscle” statement. Popular weight-loss gurus have jumped on the muscle-building-as-panacea-for-fat-loss bandwagon as well.

Dr. Mehmet Oz said in a 2007 presentation to the National Cosmetology Assn., “Muscle burns about 50 times more calories than fat does.” Bill Phillips wrote in his bestselling “Body for Life” that, “through resistance training, you can also significantly increase your metabolic rate … weight training is even superior to aerobic exercise for people who want to lose weight.” And Jorge Cruise wrote in “8 Minutes in the Morning” that his exercise regimen “will help you firm up five pounds of lean muscle within the first few weeks, allowing your body to burn an extra 250 calories per day.”

Gain 5 pounds of muscle in the first few weeks? If only.

Let’s use me as an example. I’ve added about 20 pounds of muscle through several years of hard weightlifting. If this myth holds true, I’ve gained 1,000 calories of additional resting metabolic rate each day. Well, I keep pretty close tabs on my energy balance, and I can guarantee this isn’t happening. Too bad, because those extra 1,000 calories a day could translate to a gluttonous feast of salt-and-vinegar potato chips and cookie dough ice cream.

Beyond making me the go-to guy for opening pickle jars, what other contributions are made by that extra muscle? To get the answer, I spoke with Claude Bouchard of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, La., who has authored several books and hundreds of scientific papers on the subject of obesity and metabolism. Bouchard told me that muscle, it turns out, makes a fairly small contribution to RMR.

“Brain function makes up close to 20% of RMR,” he said. “Next is the heart, which is beating all the time and accounts for another 15-20%. The liver, which also functions at rest, contributes another 15-20%. Then you have the kidneys and lungs and other tissues, so what remains is muscle, contributing only 20-25% of total resting metabolism.”

So, if you slave at weightlifting and increase your muscle mass by an ambitious 20%, this translates into only a 4% to 5% increase in RMR. Since a 200-pound man has an RMR of roughly 2,000 calories, a 20% increase in muscle mass equals only an 80- to 100-calorie increase.

For fun, let’s run the numbers in even more detail, adding the role played by body fat. Bouchard sent me a follow-up email explaining that — based on the biochemical and metabolic literature — a pound of muscle burns six calories a day at rest and a pound of fat burns about two calories a day, contrary to what the myth states. So, muscle is three times more metabolically active at rest than fat, not 50 times.

Again, let’s use me as a guinea pig and do the math. The 20 pounds of muscle I’ve gained through years of hard work equate to an added 120 calories to my RMR. Not insignificant, but substantially less than 1,000. However, I also engaged in a lot of aerobic activity and dietary restriction to lose 50 pounds of fat, which means I also lost 100 calories per day of RMR. So, post-physical transformation, my net caloric burn is only 20 calories higher per day, earning me one-third of an Oreo cookie. Bummer.

Don’t think I’m down on weights; I lift four hours a week because it’s awesome. It makes me stronger, increases my bone density and improves the strength of my connective tissues. It hardens me against injury from other activities. And my wife says that it makes me pretty from the neck down.

Bill Phillips told me through an assistant that weightlifting is better for fat loss because “each new pound of muscle tissue increases chronic total energy expenditure/metabolism” and that “aerobic exercise alone does not offer this benefit.” However, a sizable body of research shows that intense aerobic activity like running burns twice as many calories per hour as hard weightlifting, and the metabolic boost from added muscle is not nearly enough to compensate for this difference.

(I should note that Phillips and I are on the same general side in that we both recommend a combination of aerobic training and weightlifting.)

But wait! When you factor in “after burn,” couldn’t weightlifting still be some miracle calorie-consumer? Sorry, Conan, but after-burn — technically called excess post-exercise oxygen consumption, or EPOC — does exist, but only to a small degree. As I’ve covered in an earlier column, the EPOC of interval training is insignificant. And the same holds true for weightlifting.

A quick scan of the research:

• In 1995, researchers at the University of Limburg in the Netherlands published a study in Medicine & Science in Sport & Exercise on 21 male subjects and determined that weight-training “has no effect” on RMR.

• In 1994, researchers at the Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University in Denmark compared 10 bodybuilders with 10 lean (you are so puny!) subjects. Published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, the report found that intense weight-lifting did not result in any measurable EPOC.

• In 1992, researchers from the University of Texas at Austin compared intense weightlifting with intense aerobic exercise on 47 males and reported in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition that “RMR did not significantly change after either training regimen.”

Certainly the act of weightlifting burns calories, but intensity makes a big difference. In 1988, researchers at the University of Alabama in Birmingham published a study in the Journal of Applied Sport Science Research that used 17 subjects to compare the caloric burn of light versus heavier weightlifting.

When accounting for the same total volume of weight lifted (lifting 100 pounds three times is the same “volume” as lifting 300 pounds once), they found that when people lifted at 80% intensity, they burned three times as much energy as lifting at 20% intensity.

All of this, in any case, ignores the most important part of weight loss: what you eat. “The bottom line is that weight loss is 90% about diet,” obesity researcher Dr. Sue Pedersen, a specialist in endocrinology and metabolism in Calgary, told me. “The studies show that exercise alone is not going to result in weight loss.”

In other words, hours of running and weightlifting won’t burn your belly fat if you fuel that exercise with Haagen-Dazs.

April 8, 2011

“Vegetarian” Diets Reduce Heart Risks

Eating a meat-free diet may lower your risk of developing heart disease, suggests a new study, helping to lessen the likelihood of metabolic syndrome.

Eating a meat-free diet may lower your risk of developing heart disease, suggests a new study, helping to lessen the likelihood of metabolic syndrome.

Metabolic syndrome is a collection of diseases that contribute to cardiovascular disease, including diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure.

Researches found vegetarians had better blood sugar, blood fat, blood pressure, waist size, and body mass measurements than non-vegetarians.

In the study, 23 out of every 100 vegetarians were found to have at least three metabolic syndrome factors, compared with 39 out of every 100 non-vegetarians and 37 out of every 100 semi-vegetarians.

For the study, published in the journal Diabetes Care, scientists analyzed the diet of three different groups of people: vegetarians, non-vegetarians, and semi-vegetarians; in total, more than 700 adults.

The researchers used a questionnaire to obtain information on participants’ eating habits. People were classified as vegetarian, eating meat less than once a month; semi-vegetarian, eating meat less than once a week; and non-vegetarians. However, the term “vegetarian” is incorrectly defined; true vegetarians never eat meat.

Results showed vegetarians had an average body mass index (BMI) of 25.7. Unlike non-vegetarians who had an average BMI close to 30. Semi-vegetarians’ BMI fell between the vegetarians and non-vegetarians.

A BMI between 25 and 29 is considered overweight and a BMI from 30 and up is obese. Normal weight is between 18.5 and 25.

The findings remained steady when researchers combined all the readings to determine the risk of metabolic syndrome.

In 2008, Vegetarian Times reported that 7.3 million Americans follow a vegetarian diet: 59% are female, 41% are male. As of 2009, the total U.S. population was nearly 308 million.

According to the American Heart Association, a vegetarian diet – with its heavy vegetable consumption and low intake of saturated fat from animal products – has been shown to reduce the risk of heart disease, heart attack, obesity, high blood pressure, and some forms of cancer.

Article courtesy from diet-blog

Image courtesy from first reason blog

March 29, 2011

Sleep patterns affect weight loss

Managing sleep and stress levels can help in the battle against obesity, according to scientists in the US.

People getting too little or too much sleep were less likely to lose weight in a six month study of 472 obese people.

Their report in the International Journal of Obesity showed that lower stress levels also predicted greater weight loss.

A UK sleep expert said people need to “eat less, move more and sleep well”.

Approximately a quarter of adults in the UK are thought to be clinically obese, which means they have a Body Mass Index greater than 30.

Nearly 500 obese patients were recruited for the first part of a clinical trial by the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research in the US.

For six months they had to eat 500 fewer calories per day, exercise most days and attend group sessions.

Weight loss

The authors report that “sleep time predicted success in the weight loss programme”.

People with lower stress levels at the start also lost more weight.

The researchers added: “These results suggest that early evaluation of sleep and stress levels in long-term weight management studies could potentially identify which participants might benefit from additional counselling.”

Dr Neil Stanley, from the British Sleep Society, said the sleep community had been aware of this for a while, but was glad that obesity experts were taking notice.

“We’ve always had the eat less move more mantra. But there is a growing body of evidence that we also need to sleep well”, he said.

“It’s also true that if you’re stressed, then you’re less likely to behave, you’ll sit at home feeling sorry for yourself, probably eating a chocolate bar.”

Dr David Haslam, chair of the National Obesity Forum, said: “It’s a great idea to find predictors of who will respond to therapy, if this is a genuine one.”

Original artwork and article courtesy from: BBC News

February 26, 2011

Many stick with fast food after heart attack: study

It would seem logical for patients who have had a heart attack to cut back on fast food.

It would seem logical for patients who have had a heart attack to cut back on fast food.

Some devoted fast food eaters do. But six months later, more than half can still be found at their favorite fast food places at least once a week, according to a study in the American Journal of Cardiology.

Of nearly 2,500 heart attack patients studied by John Spertus, at the University of Missouri at Kansas City, 884 — or 36 percent — reported in a survey while still hospitalized that they had eaten fast food frequently in the month before their heart attack. “Frequently” was defined as once a week or more.

When Spertus and his colleagues checked back six months later, 503 were still eating fast food every week.

“Fast food consumption by patients with AMI (acute myocardial infarction) decreased 6 months after the index hospitalization, but certain populations — including younger patients, men, those currently working, and less educated patients — were more likely to consume fast food, at least weekly, during follow-up,” he wrote.

“Novel interventions that go beyond traditional dietary counseling may be needed to address continued fast food consumption after AMI in these patients.”

But the study showed that older patients and those who had bypass surgery were more likely to be avoiding fast food six months later.

The survey did not ask what menu items people ordered, and some in the restaurant business have pointed out that fast food isn’t always limited just to burgers and fries.

But Spertus and his colleagues pointed out that the people in their study who kept eating fast food tended to have health profiles “consistent with selection of less healthy options.”

Nine out of 10 patients in the study received dietary counseling before they left the hospital, but this didn’t seem to affect that odds that frequent fast food eaters would improve their diets, and Spertus said this showed they needed more education after leaving the hospital.

“The problem is that patients are absorbing so much information at the time of their heart attack, that I just don’t think they can capture and retain all the information they’re getting,” he told Reuters Health.

Fast food restaurants in the United States will soon post calorie, fat, sodium and other nutritional information on their menus, as required by the health care law passed last year.

Already, cities such as New York and Philadelphia mandate calorie counts on menus.

—

Source: http://bit.ly/eAnRdI

Image Courtesy from: Marketingpower.com

February 25, 2011

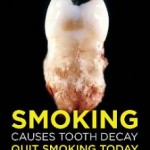

New York mayor bans smoking in parks, beaches

New York: the city that never smokes. Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed a law Tuesday banning smoking in parks, beaches and busy gathering places like Times Square, the health department said.

New York: the city that never smokes. Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed a law Tuesday banning smoking in parks, beaches and busy gathering places like Times Square, the health department said.

The law, approved by the City Council at the start of February, will be backed up with $50 fines, the department said.

It will take effect in 90 days, ending smoking in parks, pedestrian zones and 14 miles (23 kilometers) of beaches. Smoking is already forbidden in office buildings, bars and restaurants.

Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said the rules would make those public spots “healthier places than ever. I encourage those still smoking to take this opportunity to quit smoking today.”

—

Article courtesy from Yahoo! Health

Image courtesy from Gossip Jackal

February 12, 2011

United Airlines Charges Extra For “Larger” Customers

United Airlines passengers who do not meet specific size limits may be forced to shell out a bit more cash—or remain grounded, according to information posted on the company’s website. The new requirements were implemented to enhance “the comfort and well-being of all customers aboard United flights.” The website states that passengers must be able to

United Airlines passengers who do not meet specific size limits may be forced to shell out a bit more cash—or remain grounded, according to information posted on the company’s website. The new requirements were implemented to enhance “the comfort and well-being of all customers aboard United flights.” The website states that passengers must be able to

- fit into a single seat in the ticketed cabin;

- properly buckle the seatbelt using a single seatbelt extender; and

- put the seat’s armrests down when seated.

A United customer who cannot meet the requirements will be given a few options, depending upon seating availability. If there are available seats on the purchased flight, the passenger will be relocated next to an empty seat. If no seating is available, the passenger will be required to “purchase an upgrade to a cabin with available seats that address the above-listed scenarios or change his or her ticket to the next available flight and purchase a second seat in addition to the one already purchased.” Customers who do not meet the criteria and choose not to purchase an extra seat will be barred from boarding.

February 2, 2011

Envisioning Single-Serving Sizes

Consumers are starting to realize that healthy eating is all about moderation. They have been bombarded with advice about portion control and encouraged to stick to single servings. But studies show that many people remain confused about what these terms mean.

According to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), a portion refers to the amount of food you choose to eat, whereas a serving is used to describe the recommended amount of food you should eat at a given meal.

Still confused? Well, so are many of your clients. Since a picture is worth a thousand words, imagery may be the best way to teach them the difference. Use these visual examples provided by the NHLBI to show your clients what a serving really looks like.

—

source: IDEA Fitness

February 1, 2011

Eating Behaviors & Girls’ Bone Loss

Adolescent girls who compete in athletic events sometimes fall victim to disordered eating, which has been linked to low bone mineral density (BMD). To explore the specific eating behaviors that lead to low BMD, researchers recently compared the attitudes and concerns of teenage girls who were endurance runners.

The study participants were 93 female competitive cross-country runners ranging in age from 13 to 18. The adolescents were assessed for different types of disordered eating, such as weight concern, shape concern, eating concern and dietary restraint, along with BMD history.

After adjusting for other variables, such as menstrual irregularities, the researchers found that dietary restraint was the behavior most associated with low BMD. Concerns regarding weight, shape and eating (or any combination of these three concerns) were not significantly associated with low BMD.

Reporting in the January issue of The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, the researchers concluded that “in adolescent female runners, dietary restraint may be the disordered eating behavior most associated with negative bone health effects.”

—

source: IDEA Fitness

January 21, 2011

Salad Sabotage!

Think that you are being virtuous when grazing at the salad bar instead of grabbing a burger for lunch? Well, think again: Many of the items lurking under that plastic protective covering are actually quite high in calories and/or fat. Here are some of the culprits to watch out for at your favorite salad counter:

Dressings. Avoid French, Italian and Russian dressing, which contain about 65 calories per tablespoon, and don’t even think about ranch dressing, which packs in a whopping 90 calories per tablespoon.

Coleslaw. Hard to believe a 6-ounce serving can contain 150 calories!

Cottage Cheese (Full Fat). Those 120 calories per half cup can put the cottage cheese on your thighs in a hurry.

Egg Salad. At 345 calories per 4-ounce serving, you should at least get some bacon on the side, no?

Bacon Bits. Speaking of bacon, a mere tablespoon of these little buggers will set you back 30 calories.

Peas. One half cup contains 70 calories, so use sparingly.

Croutons. Easy on those tablespoons, each of which contain 20 calories.

Sunflower Seeds. These crunchy toppings weigh in at 175 calories per ounce.

—

Source: CalorieKing.com